M&A Monday: Sellers' Attempt to Limit Liability: Indemnification Caps*

An explanation of indemnification caps and why the "market" position is wrong (you need to know this).

Shockingly, deals die over the cap on indemnification. This is an issue that lawyers love to argue about. They routinely bill tens of thousands of dollars going back and forth on why the indemnification cap should be 15% rather than 10% of the purchase price.

Two weeks ago, a seller’s lawyer (I’ll call Bob), told me that our requested cap on indemnity was a “walk-away issue” and a “non-starter”. When I questioned whether the seller would really walk away over a difference in indemnity caps, Bob said, absolutely.

A savvy buyer must understand indemnification caps and be able to discuss this issue directly with a seller so that Bob’s alarmism does not kill a good deal. This is often raised at the LOI stage.

I did a deep dive into Caps and Baskets, HERE. Go read that first: https://x.com/Eli_Albrecht/status/1734314621102669994?s=20

As a quick review, unlike buying real estate property, a buyer of a business is fully reliant on the seller for accurate due diligence materials. Thus, a good purchase agreement will ask the seller to make representations and warranties - promises that certain things about the business are true (e.g., the financial statements are correct, there is no pending litigation, no material customers are leaving).

After closing, if one of those promises turns our to be incorrect and results in a loss to the buyer after Closing (as it relates to pre-closing periods), the Buyer can get money back to cover that loss.

For example, if the seller knew that there as a pending litigation, but promised there was none. Then, after closing someone files a law suit that costs $1 million, the buyer can recover that loss from the seller.

Traditionally, in private M&A, there is a liability Cap on non-fundamental representations (less core promises - see prior post).

In short, a Cap on indemnity refers to the maximum liability a seller will have if they misrepresented non-fundamental representations. Non-fundamental reps traditionally include, financial statements, undisclosed liabilities, material contracts, sufficiency of assets, intellectual property, inventory, insurance, litigation, compliance with laws, etc. Remember, these are promises the seller is making about the condition of the business that is being acquired.

This means that if something goes wrong after closing resulting from a misrepresentation in any of the non-fundamental reps that costs more than the cap, Seller is only responsible up to the Cap. For example, let’s say the seller provided financial statements to the business that were incorrect. This resulted in a $2m post-closing loss. If the purchase price is $10 million and the cap is set to $1 million (10%), the seller will only be responsible for up to $1 million (minus any deductible basket). Thus, the buyer will have to eat $1m in losses due to the seller’s misrepresentation. Fraud and willful misrepresentation are not usually subject to a cap.

This is why lawyers aggressively argue over caps.

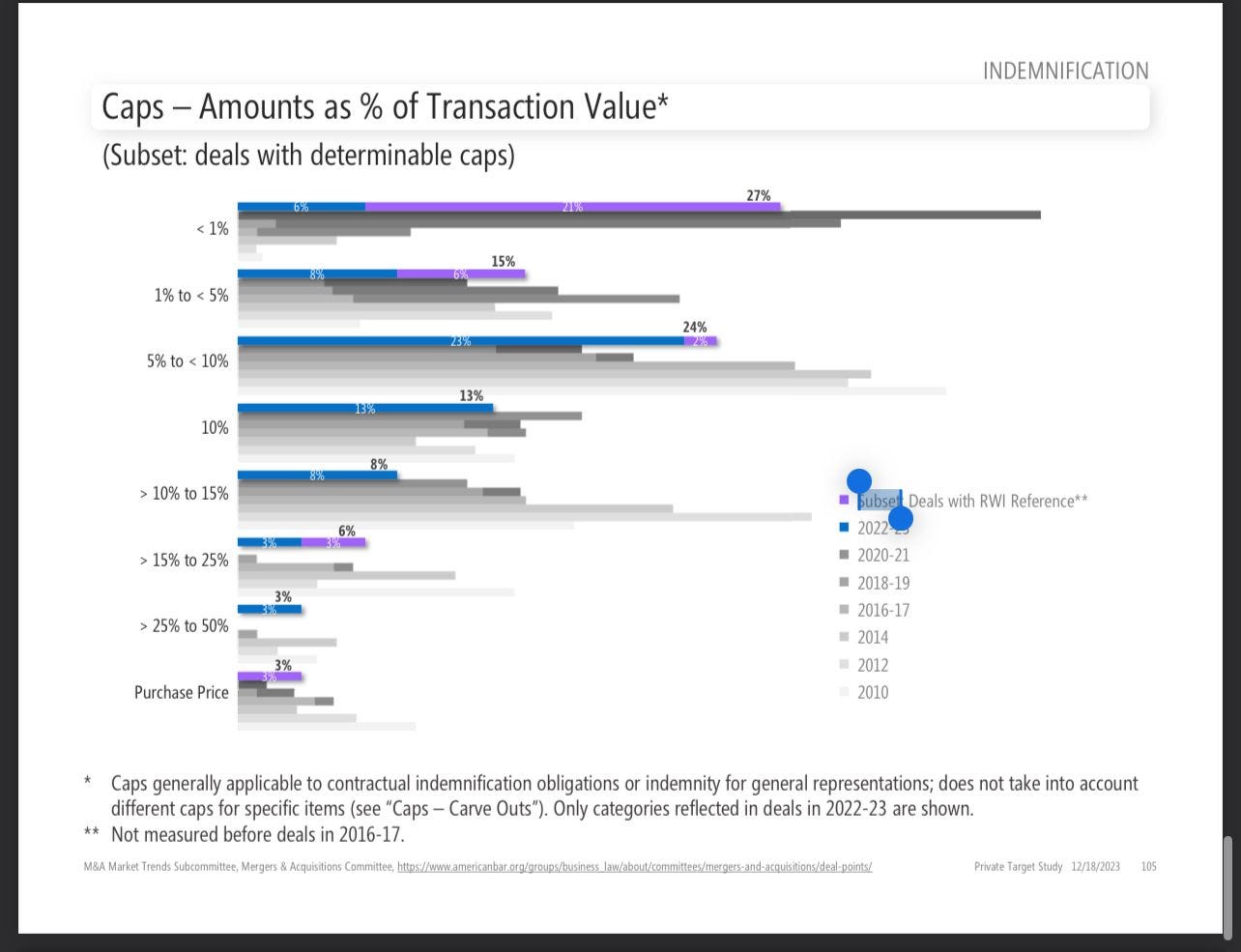

Where should the Cap be set? Most lawyers will tell you the “market” for a cap is around 10% - 15% of the purchase price. That data over the past 10 years seems to support this on larger deals. There is no good data on smaller deals, although at SMB Law, we have a very good idea of the market on deals less than $50m.

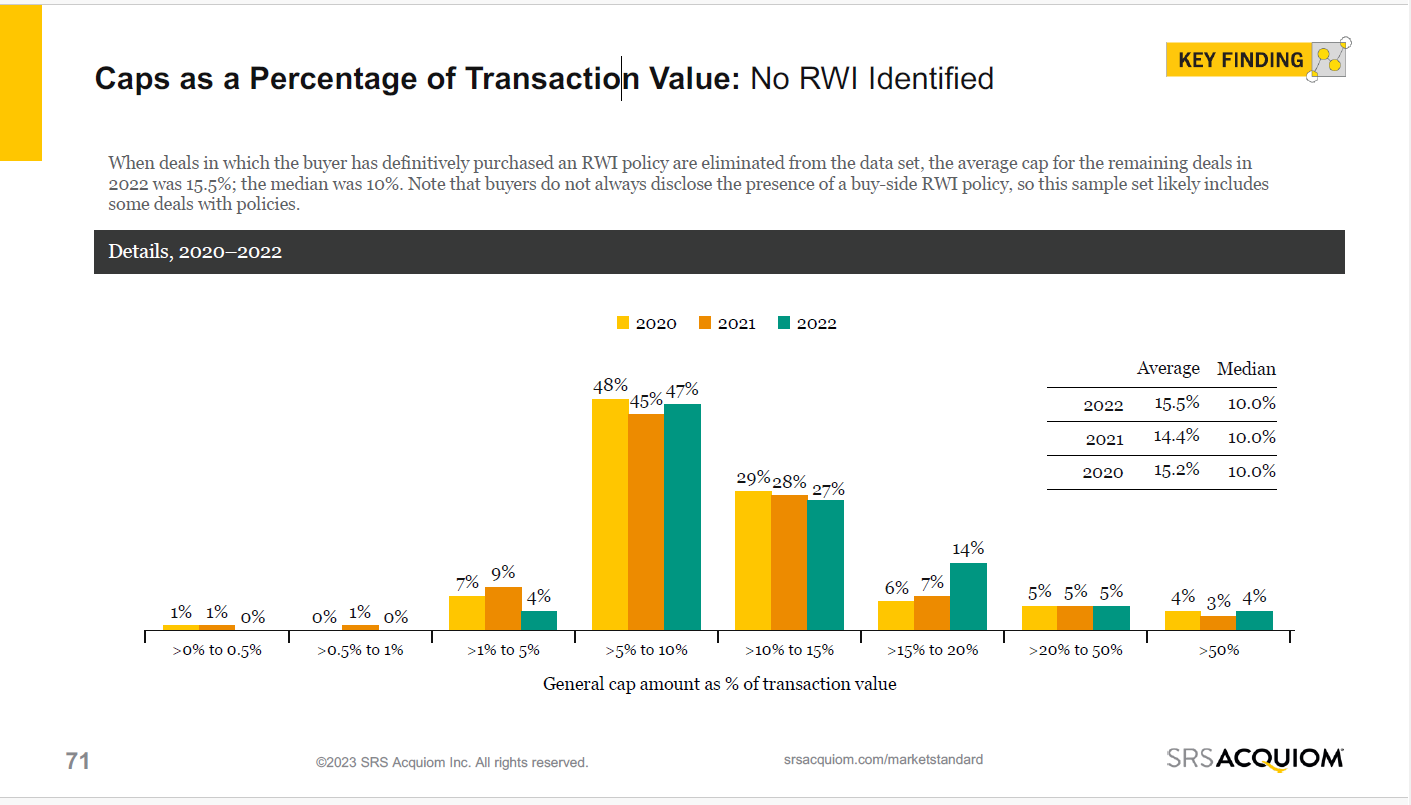

On larger deals, the “market” for M&A deals in 2022 was around 5%-10% (47% of deals). However, 50% of M&A deals in 2022 were above 10% cap (27% of deals were between 10%-15% cap, 14% of deals were between 15%-20% cap, 5% of deals between 20% - 50% cap, and 4% of deals above 50% cap (no RWI).

Three notes on this data:

(1) in 2022, more M&A deals had caps above 10% than below; (2) this data is from 2022 and shows an increase in caps from 2021. In 2023 M&A was slower shifted to a buyer’s market. We will likely see much higher caps in the 2023 data; and (3) this data is all from deals $100m+.

A cap essentially shifts all risk of liability above the cap ($5.5 million in our example) to the buyer.

From a philosophical perspective, it is unclear to me why a buyer should assume a seller’s misrepresentations above a certain threshold. In our example above, why should buyer be stuck with a $4.5m loss when the buyer paid $55m for the business?

Business decline is the risk of buying a business, but the seller's intentional or unintentional misrepresentation is not a risk that should be assumed.

Last week I suggested a 60% cap on non-fundamental reps and the seller’s lawyer said on a call with the clients, “Eli is insane. This is the most ridiculous thing I have seen in 20 years.”

I responded that if he bought a car that didn't work, should the car dealership only be responsible for losses up to 10% of the vehicle?

To understand why caps average less than 10%-15%, let’s take a look at the history of how caps developed.

In 2008 caps averaged almost 22% (including RWI (discussed below), so probably higher for non-RWI). Over the past 15 years, interest rates and economic recovery drove a private equity frenzy. Debt markets were lending massive leverage for leveraged buy-outs assuming economic growth and continued low interest rates. It was a perfect seller’s market. For 13 years, private equity groups fell over themselves bidding on targets. I worked on many of these deals.

Sellers had more leverage in the private M&A market. So, they simply demanded buyers assume more liability (lower caps).

This also came from a new private M&A process that proliferated during this boom market. On larger M&A deals there is an auction process. Seller drafts a purchase agreement and sends it to interested buyers. It is almost always a “public-style” deal where buyer assumes all risk. Then, the buyer marks up the purchase agreement and sends it back and seller decides which buyer they like. This resulted in buyers competing by requesting lower and lower caps (or tiny caps and using Rep and Warranty Insurance to stand behind the seller’s promises). This drove down the market averages for Caps, but is not representative of deals below $100m.

I believe on sub-$100m deals, the buyer’s liability (Cap) should be capped at the purchase price. If $55m is paid for business and there is a $55m loss, why should the seller keep any part of the purchase price paid to them? Why should the seller not be responsible for their misrepresentations?

Given that Eli says the Cap should be the purchase price and seller’s lawyer will call you INSANE if you ask for that, how do you determine a proper cap?

I encourage you to disregard the “market” or “average” cap on a small deal. Instead, ask yourself, how comfortable am I with the business that I am buying? If there is a post-closing loss, how much risk am I willing to assume and how much should the seller assume?

My opening position is that the seller should ensure that all of their representations and warranties are correct and then fully stand behind those reps. The cap should be the purchase price.

Each deal is different. A cap should reflect the level of actual risk and liability of the company you are buying.

Understand the following factors:

(1) Does the seller have proper controls and professionalization to reduce risk of liability post-closing. We cannot ever perform enough diligence to get fully comfortable with assuming all the risk of liability after closing.

(2) What is the industry risk? If this is a SAAS business it may have lower risk than a manufacturing business.

(3) How forthcoming has seller been with diligence documentation? Has seller been able to produce adequate financial and legal diligence?

Seller’s Position.

Here are the arguments that sellers make to limit their liability (each can be refuted).

There are 30 pages of representations and warranties, we cannot possibly account for all of them and do not want to be responsible for missing something.

Nepharious buyers can use indemnifications after closing to claw back the purchase price.

It is not market (this is the most common argument and the one I find least compelling).

Three closing notes:

Usually reps and warranties are divided into fundamental and non-fundamental. It is generally understood that fundamental reps are not subject to a Cap and non-fundamental are. However, if you want to accept a Cap, but are concerned about specific issues, you can make a rep fundamental or make a new category with its own cap. For example, if you are concerned about employee classifications, you can agree to a non-fundamental cap of 10%, but employment issues are subject to an 80% cap. You can get granular on what is subject to caps and what is not (same with Survival, but that is a different post). Be careful of overcomplication.

As a buyer, I include our position in the LOI (cap of purchase price on all representation and warranties), however, if seller’s lawyer pushes back I ask to defer this conversation until due diligence. This way, I can better determine the risk profile of the business and how hard we should push on this issue.

Representation and Warranty Insurance is sometimes used to cover any non-disclosed post-closing losses that seller would otherwise have to cover. However, insurance does not cover known or disclosed issues and still subject to caps and baskets (they just tend to be lower). I don’t like RWI for a few reasons, but that is also for another post.

*I will return to my series walking through each aspect of the acquisition process (I was up to LOI terms), but will often take breaks for deep dives into issues like this as they arise.

Interesting piece. As one who most often sits on the Seller’s side of the table, I thought I’d add to the Seller’s counsel argument. If a Buyer proposed uncapped indemnification obligations or even a cap that was 4x what is considered reasonable in lower middle market deals, I would object, but not only for the reasons you suggest in your summary. I would counsel my client that the Buyer is either attempting to shift nearly all of the risk of its diligence back onto Seller, or they’re sandbagging (and you would have struck the anti-sandbagging position after our first turn). Either way, it raises questions about the Buyer and undermines trust right out of the gate.

Take your car analogy. If I’m selling my car and I allowed the Buyer to take it to her mechanic, and the mechanic looks at it and says it is in the condition I represented it to be, should I still be on the hook for a condition that is discovered after I sold it, even if I wasn’t aware of and Buyer’s mechanic didn’t even pick it up? (Obviously this analogy has some limitations, but hopefully you see my point).

Consider how this works in earnouts, which are part of many lower-middle-market deals. Seller has a substantial portion of the purchase price tied to Buyer’s ability to run the business profitably post-closing. But Buyers resist restrictions that would require them to continue to run the business as it is currently conducted, or even agree that if they deviate from past operational practice they won’t hold it against the Seller for purposes of the earnout. So by taking a “no cap” position on indemnification liability, and simultaneously taking a “no responsibility” position on preserving the earnout potential, it undermines trust right out of the gate.

I understand your point as Buyer’s counsel - the Seller should stand behind all of their reps and warranties unconditionally, and if anyone should bear the risk it should be the Seller. But if this is a relationship where the Seller isn’t just walking away - either because they’re staying involved in the business, have an earnout, or rolling equity - I think taking such an aggressive position on the indemnity cap sends the wrong message.

Thanks again for posting this!